Influenza is easily spread from person to person. It can cause mild to severe illness and at times lead to death.1-3

Most experts think that influenza viruses are spread mainly by droplets made when people with flu cough, sneeze, or talk. These droplets can land in people’s mouths or noses or can be inhaled into the lungs. Putting physical distance between yourself and others can help lower the risk of spreading a respiratory virus.2

Less often, a person might get influenza by touching a surface or object that has flu viruses on it and then touching his or her own mouth or nose.2

Most healthy adults may be able to infect other people with flu beginning 1 day before symptoms develop and up to 5 to 7 days after becoming sick. Children may pass the virus for longer than 7 days.2

Symptoms typically begin two days after the virus enters the body, but can range from 1-4 days, though some people can be infected with the flu virus and show no symptoms. Despite not showing symptoms, people may still spread the flu virus to their close contacts.2

While there are several types of influenza viruses, two are predominantly associated with human infection: type A and type B. Certain groups are more likely to get severe illness from influenza, such as adults age 65 years and older, as well as young children, babies, pregnant people, and people with chronic health conditions.1,3-4

Type A viruses specifically have different subtypes based on the two different proteins they express on their surface: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). For example, influenza A (H3N2) is a type A virus that has H3 and N2 on its surface.3,5 Over time as the virus replicates, small changes in the genes of influenza can accumulate and result in changes to the viruses, which make them antigenically different from previously circulating flu viruses.6-7 This gradual change is referred to as antigenic drift.7 As a result of antigenic drift, flu vaccines are updated every season to provide protection against flu viruses most likely to cause illness in the upcoming flu season.6-7 Of note, occasionally more abrupt changes in the influenza virus can occur as well, known as antigenic shift. Antigenic shift occurs when an influenza virus acquires a new hemagglutinin protein and/or new hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins.7 Antigenic shifts can result in influenza pandemics if the new flu virus is able to easily spread from person to person and if most or all of the population does not have antibodies to the new shifted flu virus.7

The clinical presentation of influenza ranges from asymptomatic infection or an uncomplicated influenza to a severe illness with potentially fatal complications.8

In older adults, influenza sometimes presents differently than it does in other age groups.9

Older adults may experience malaise instead of the sudden onset of high fever typical in children and younger adults.9

Stomach pain, diarrhea, and nausea are more frequent symptoms in older adults and younger children than in some other age groups.9

Runny nose, sore throat, and nasal congestion are all less frequent symptoms in older adults than in other age groups.9

SERIOUS COMPLICATIONS

Complications from influenza can lead to life-threatening conditions in older adults. Serious complications include the following9:

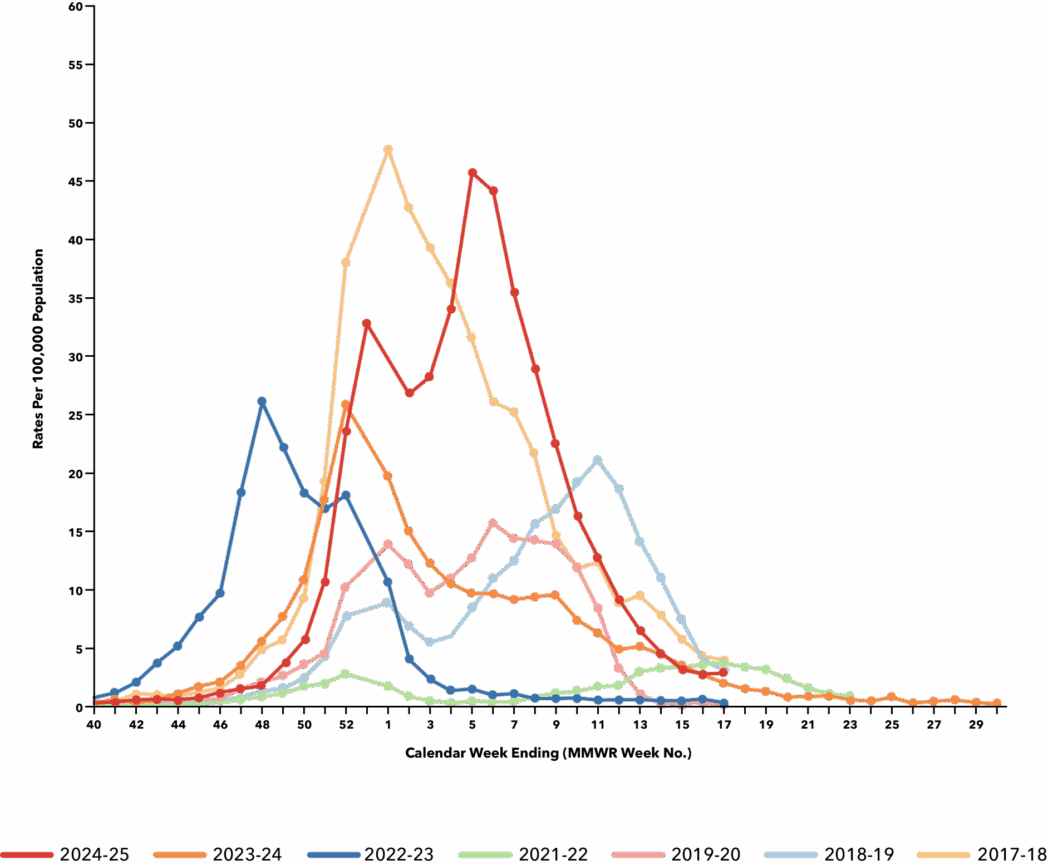

TIMING OF FLU HOSPITALIZATION IN ADULTS AGE 65 YEARS AND OLDER DURING 2016 – 2025 FLU SEASONS 10

The peak of the flu season varies annually but typically occurs between December and February in the northern hemisphere. As such, ideally, vaccination should occur before the end of October and continue throughout the influenza season as long flu viruses continue to circulate.1

EVIDENCE-BASED RESOURCES

From the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Influenza ACIP Vaccine Recommendations (web page)

- Influenza (Flu) Information for Health Professionals (web section)

- Flu & People 65 Years and Older (web page)

- Flu Resource Center (web section)

- Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine Preventable Diseases (The Pink Book); Chapter 12: Influenza (web page)

From Immunize.org

Immunize.org and CSL Seqirus are not responsible for content found at external links.1. Grohskopf LA, Ferdinands JM, Blanton LH, Broder KR, Loehr J. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2024–25 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2024;73(RR-5):1-25.doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7305a1. 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How flu spreads. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spread/index.html. Published September 17, 2024. Accessed October 14, 2025. 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About influenza. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/index.html. Published September 11, 2024. Accessed October 14, 2025. 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People at increased risk for flu complications. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm. Published September 11, 2024. Accessed October 14, 2025. 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Types of influenza viruses. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses-types.html. Published September 26, 2025. Accessed October 14, 2025, 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key facts about seasonal flu vaccine. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines/keyfacts.html. Published September 17, 2024. Accessed October 14, 2025. 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How flu viruses can change: “Drift” and “shift”. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/viruses/change.html. Published September 17, 2024. Accessed October 14, 2025. 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Signs and symptoms of flu. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/signs-symptoms/index.html. Published August 26, 2024. Accessed October 14, 2025. 9. National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Call to action: Reinvigorating influenza prevention in US adults age 65 years and older. https://www.nfid.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/flu-65.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed October 14, 2025. 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations. https://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html. Published September 20, 2025. Accessed October 14, 2025.